At the age of nineteen I left Israel to take up university studies in Germany. It was the early 1980s. Israel had launched a military offensive in southern Lebanon and the only way to avoid serving in the army was to leave.

My grandmother, who was raised in the German-speaking principality of Danzig and had narrowly escaped the Holocaust, cautioned that in Europe I would experience antisemitism. I dismissed her warnings. They struck me as out of date. Like other left-wing activists in Israel I regarded antisemitism as an experience that was largely confined to the past and was now being mobilised to justify military adventurism and reluctance to engage in political compromise.

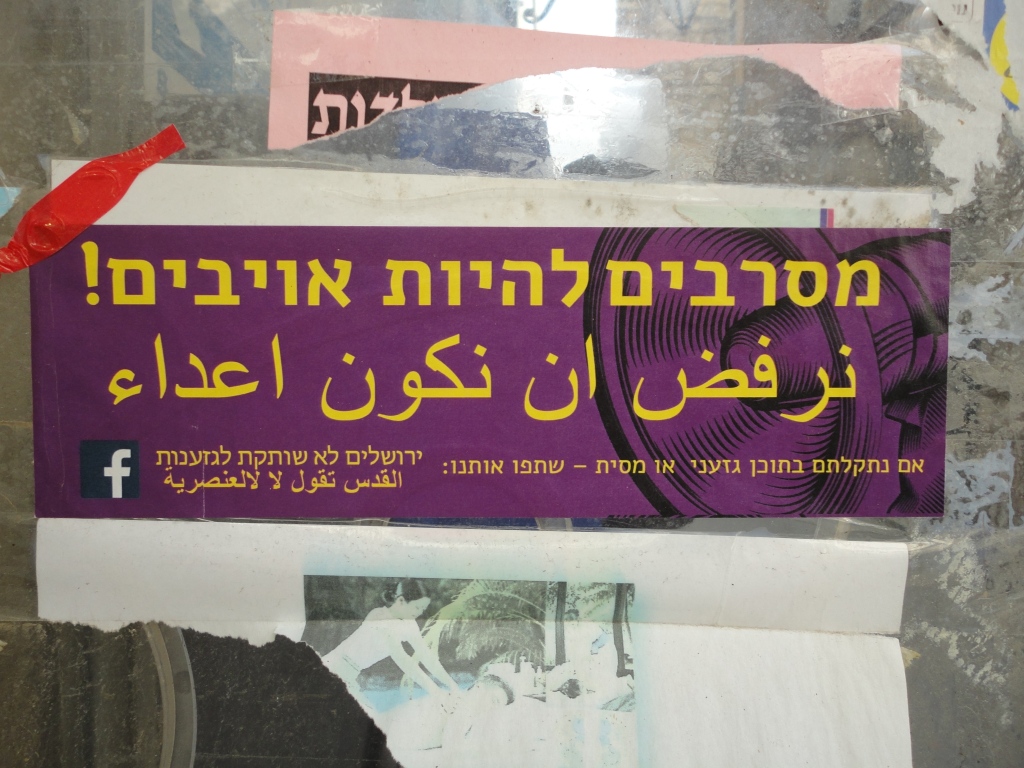

Soon after arriving in the university town of Tübingen I joined campaigns to end Israel’s presence in southern Lebanon and its occupation of the Palestinian territories in the West Bank and Gaza. I continued to support Israeli-Palestinian partnerships that entertained visions of a bi-national state. I befriended Palestinian refugees from Lebanon and Syria and assisted them with their applications for asylum. I shared public platforms with Palestinian activists and co-authored discussion papers with exiled Palestinians.

I worked closely with another Israeli, a veteran of the anti-Zionist group Matzpen, fifteen years my senior, who became a political mentor to me. Together we approached the Student Union’s executive committee on numerous occasions to promote pro-Palestinian events. We were welcomed there with open arms.

Then, in late 1984, a group of Jewish protestors in Frankfurt tried to block the staging of ‘The garbage, the city, and death’ by playwright Rainer Werner Fassbinder. The piece depicted a Jewish property developer who was despised by local residents and subjected to the boldest antisemitic remarks including “it’s a shame they didn’t gas him along with the others”. Fassbinder, no longer alive by then, was idolised by the German Left. His fans explained the play as an attempt to draw attention to inequalities. But Jews found the words offensive. Critical voices outside the Jewish community denounced the urge to challenge what had finally, after centuries, become a taboo on publicly articulating anti-Jewish hatred.

We approached the Student Union and asked them to condemn the content of the play. Rather than support censorship or boycott we called for the performance to be accompanied by an open discussion about antisemitism – a tool to raise awareness. But our comrades brashly dismissed our request, lecturing us about Israel’s policy of aggression.

It was my first encounter with double standards, hypocrisy, and the Left’s reluctance to confront antisemitism. It was a time when activists against South African apartheid found themselves on the same side as some two-dozen African despotic regimes. Yet the comrades at the Student Union cited Israel as a reason not to confront antisemitism in the very country where it had shown its most horrendous face ever. As petitioners, our critical stance on Israeli policy made no difference.

In the mid 1990s I took up an academic position at a UK university. My grandmother asked whether my colleagues at the department knew that I was Jewish and whether they accepted me regardless. I tried to explain that Europe had changed since her times and that antisemitism was history.

Then things started to happen. During a lunch time conversation a colleague argued passionately that cultivating sidelocks among Orthodox Jewish boys amounted to child abuse and should be outlawed. A few years later that same person, now in a middle management role, teased me whether, when I met with Jewish students during my consultation hour, I talked to them about “killing Arabs”.

I witnessed a campaign to ban the Jewish Student Society arguing that it was a ‘Zionist’ group, that Zionism constituted racism, and that the society was therefore in violation of the Student Union’s constitution. I was the only staff member, along with an American colleague, who joined a campus rally against the proposed ban. I heard staff mockingly dismiss complaints from female Jewish students that they were verbally abused as ‘Zionists’ when wearing traditional dress and necklaces carrying the Star of David. I was forcefully told off by a colleague for suggesting such grievances should be taken at face value.

When my Syrian PhD student reported being harassed by other Arab students for working with an Israeli, the Postgraduate Student Advisor suggested the student should change supervisor. Then a young Israeli colleague was asked to withdraw from another PhD panel because “it would not be appropriate for an Israeli to advise a Jordanian student”. When I heard about the incident I expressed my dismay to management. I was reassured that “nobody should be discriminated based on their ideology”; to them being Israeli was not a nationality but an ideology. I asked that the unit’s position be made clear. In response I was reprimanded for being unreasonably persistent and using “inappropriate tone”.

In a book chapter with a leading academic publisher I devoted a few lines to critiquing a hypothesis on a linguistic matter on which I was a recognised authority. The person whose work I had critically referenced reacted by posting a comment on a website devoted to the boycott campaign against Israel (BDS), writing that “the Israeli Yaron Matras” had been hostile to them because they weren’t Jewish.

Already a professor, I notified a colleague, as a courtesy, that I had enquired with an internationally renowned linguistics scholar based in Israel whether they might wish to give a seminar at our department during their next UK visit. My colleague hurried to denounce me to management and within a few hours I received an email threatening me with disciplinary action for “committing the university to a political position”.

I had been a regular contributor to an online policy blog hosted by an academic institution. I produced several texts on anti-Roma racism, a topic in which I had an interest, and some on multilingualism, my field of research. In the summer of 2018 I submitted a post about the antisemitism debate in the Labour party focusing on the semantics of using ‘Zionist’ as placeholder for ‘Jew’. My text was rejected with the argument that I was not an expert on antisemitism. Then, after I pointed out that there was a linguistic angle, they said the text was fine but there was no capacity to publish during the summer break. A week later, when the break was over, they said the publication guidelines had just been amended and my text no longer complied. When I decried an apparent lack of sensitivity towards antisemitism I was accused of insulting my addressee.

After the Brexit referendum a group of researchers argued that language learning should be used to support Global Britain, help boost security and “soft power” and serve “progressive patriotism” (a notion that has since been linked to white supremacism). They wanted a government language coordinator to be based at the country’s spy agency. I was part of the same research scheme but I was not enthusiastic about that particular line of argument. Instead I called to recognise Britain as a multilingual society and to adopt a domestic language policy. A colleague declared me an opponent. Together with a few close allies they launched a defamation campaign against me. They incitefully suggested that I was trying to undermine the project, to bring my institution into disrepute and to destroy the discipline of Modern Languages in order to secure funding for myself.

In a series of emails and statements they said I was cunning, disloyal, all-powerful and controlling, beyond scrutiny and out of control, causing people to fall ill, outrageous, malicious, disruptive, unpleasant, unpredictable and mercurial, delusional, paranoid, muddying waters with propaganda and holding vendettas against those who didn’t share my narcissistic view of the world. One, an open supporter of the BDS, opined that I was argumentative and aggressive, picking on the defenceless and innocent, and then concluded that my “quirkiness” should no longer be tolerated.

It was an uninhibited cesspool flood, unleashed via institutional channels. It testified to a deeply ingrained feeling of superiority over me and depicted me as an enemy from within. It reproduced precisely the stereotypes that Kenneth L. Marcus lists in his book The Definition of Antisemitism as traits that are typically attributed to Jews: Sinister, conspirational, treacherous, greedy, criminal, power-hungry and diabolical. I shared the material with the relevant management outlets and was later rebuked for trying to damage colleagues’ reputations.

The Macpherson Report and later the EHRC concluded that the wholesale dismissal of racism is itself a form of racism and as such unlawful; but try arguing that and you get yourself into trouble. The accusation is turned around and you become the guilty party.

In 2021 a group of international academics published the Jerusalem Declaration on Antisemitism. Embroiled from the outset in a bitter competition with other definitions, most notably that of IHRA, the JDA nevertheless nicely summarised a consensus view on what it called “classic antisemitism”: The idea that Jews are linked to the forces of evil, that they possess hidden powers which they use to promote their own collective agenda at the expense of others, that they are responsible for spreading disease, that they act as “a state within a state”, that they control governments with a “hidden hand” and that they own the banks and control the media. The JDA also recognised that portraying Israel as the ultimate evil or grossly exaggerating its actual influence could be a coded way of racialising and stigmatising Jews, as is holding Jews collectively responsible for Israel’s conduct or treating Jews, simply because they are Jewish, as agents of Israel.

The antisemitism that I witnessed and experienced turned from ordinary expressions of everyday prejudice through to recurring threats of isolation and exclusion and on to systematic vilification driven by jealousy and sheer malice. At times it enjoyed protection from individuals in key managerial positions. The escalation from casual to institutional racism coincided first with the university trade union’s call for an academic boycott of Israel, which many interpreted not just as directed at Israeli institutions but as a license to target anyone whose background or identity was somehow associated with Israel or Jews. It later continued with the intensifying Othering of foreign-born actors in the aftermath of the Brexit debate and with the ideology cemented during Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour party, which insisted that complaints about antisemitism were inherently made in bad faith to silence criticism of Israel.

Since I left my university position in 2020 a surge in antisemitism on UK campuses has been identified through investigations by the Community Security Trust and Universities UK as well as reports by The Tab and Glamour magazine, among others. It was against that build up that in October 2023 students across UK campuses took to the streets to express their “joy” and feeling of “inspiration” (as a student spokesperson in Manchester put it) after Hamas murdered hundreds of Israeli civilians in a terror attack that shocked the world.

Outside academia the guard drops even further. One of my most chilling experiences was at a south Manchester sports facility. It was a random crowd of four people in their 20s and 30s. Together they represented British society’s full diversity: Muslims and Christians, men and women, two Asians, one White, one Black.

Their conversation caught my attention when one of them said that the Holocaust was wildly exaggerated since it had been logistically impossible in the 1940s to transport hundreds of thousands of people to extermination camps. Another seconded, offering that Jews used their control over politics and media to force Austria to ban Holocaust denial. That was applauded by a third, who said she grew up in North Manchester and knew all about “these bastard Jews”.

This chance party of people, all of whom will have been through the British education system, were residents of a Labour governed city that prides itself on its ethnic and cultural diversity as well as its history of progressive social movements. Yet they had no inhibition airing anti-Jewish hatred in the presence of strangers, in a publicly owned space. It wasn’t even focused on Israel.

Jews were England’s first diaspora community. Drawing on international networks of contacts their impact was innovative and profitable. They were enterprising while remaining true to themselves, participating but not assimilating, creative but ‘quirky’.

Antisemitic blood libels were recorded in England since the twelfth century. But the story of Young Hugh of Lincoln in 1255 was a turning point. Hugh was portrayed as the innocent and defenceless victim of a ritual murder by local Jews, whose scheming and exploitative behaviour had been tolerated for far too long and who were thus able to prey on others.

For the first time, the Crown took a direct interest, ordering the execution of nineteen Jews and confiscation of their property. Ultimately, the incident served as pretext for the wholesale expulsion of Jews from England in 1290.

The accusations were driven by suspicion towards the Jews and a desire to take over their assets, coupled with the inability to prove any tangible wrongdoing or violation on their part of the laws of the land.

Hugh became celebrated as a martyr, endearingly referred to as a Saint despite never attaining formal canonical status. His story is perpetuated in an antisemitic finale to Chaucer’s Prioress’ Tale. The modern song ‘Little Sir Hugh’ goes back to an English folk song about the ‘Jew’s garden’.

Antisemitism, as my grandmother was aware, is an intrinsic part of European culture. The story of Hugh repeats itself whenever a Jew is perceived as successful and becomes the subject of envy while remaining ‘quirky’. The blood libel conspiracy is needed because everyone knows that there is no actual transgression to account for.

Dealing with so-called progressive antisemitism is particularly challenging. The political Left regards anti-racism as one of its pillars, much like higher education institutions flag a commitment to diversity. Both are predisposed to denying that they may have a problem within their own ranks.

While other forms of racism are directed against those who are perpetual socio-economic victims and to whom discourses of intersectional oppression can be applied more easily, antisemitism tends to depict Jews as superior and in control.

Modern antisemitism might be described as the obsessive urge to return to the historical European normality of perceiving and depicting Jews as exploiters and oppressors. That requires the cancellation of post-Holocaust acknowledgement of Jews as victims. Israel offers an opportunity to present that impulse as tangible.

Comparisons with Nazis and Apartheid sometimes serve the Israeli Left as emotional references to a shared value compass for the purpose of sensitising and mobilising. In other contexts they are used to erase sensitivity towards antisemitic tropes and to cancel the responsibility to call them out, or even the legitimacy to do so.

In this way, Zionism is used as a weapon to exonerate antisemitism, while others use antisemitism not just to explain the historical roots of Zionism but also as a tool to exonerate actions committed in its name. Zionism and antisemitism are intertwined and entangled in an inverted relationship.

Some regard anti-Zionism inherently as an anti-Jewish ideology. But before the Holocaust most Jews were not Zionists. My grandfather left Russia for Palestine in the early 1920s. Coming from a bourgeois Jewish background he was denied the opportunity to study medicine. He turned against the Bolshevik state, embracing Zionism as a pathway to assert himself. He sought opportunities for personal development in one political process having suffered exclusion and deprivation through another. But most of his siblings chose to stay in Russia. At the time they believed in the Soviet state and they opposed Zionism. History cannot possibly label them as anti-Jewish.

What anti-Zionism means today is a matter for debate. It can mean identifying with the stance taken by my grandfather’s siblings rather than with his own. Looking forward, it can mean acknowledging that the Zionist enterprise from which my grandfather benefited has inflicted injustice and suffering on others and recognising that peace and co-existence can only be achieved if we can find a way to undo those consequences without inflicting new injustice on the community of Jewish Israelis that has since emerged. That stance, too, cannot be regarded as anti-Jewish.

As others have remarked, ‘Zionism’ has become a political, sometimes even just casual label for ‘good’ or ‘bad’. I recall my girlfriend’s mother praising us teenagers for walking all the way from a neighbouring village instead of waiting for the bus. She described our spirit of determination as “true Zionism”. By contrast, when I introduced myself to a renowned academic after their public lecture in Paris, the speaker, having identified my Hebrew name, challenged me to proclaim that I was not a ‘Zionist’ before engaging in conversation with me; it was their way of performing their progressive credentials.

As long as ‘Zionists’ and ‘Zionist Entity’ serve as token placeholders for ’Jews’ and ‘Israel’, it is understandable that many Jews and Israelis perceive rhetoric that calls to eradicate ‘Zionism’ as menacing. The calling of names also blurs the political agenda. It makes it impossible to distinguish universalist-secular democrats from violent jihadists and all-round fascists: They all rally behind the call to resist Zionism. They all use the term as a wholesale insult rather than analysis.

Intellectuals on the Israeli Left have been speaking for several decades now of a post-Zionist era. This notion is set against the view that politics, research and teaching, and the arts and cultures should all be mobilised to serve the nation-building project. It prompts us to turn our attention instead to the day to day reality of Israeli identities as a pluralistic experience.

Perhaps we can abandon the divisive rallying around ‘Zionism’, both pro- and con-. We should become agnostic of the concept and focus our conversation on practical steps towards a partnership between Israelis and Palestinians that is based on equality and personal freedoms, on pluralism, on cultural rights and communal self-determination, and on correcting historical injustices without inflicting new ones.

Both my grandparents regarded antisemitism as a pathology that was eternal and could not be eradicated. It was that conviction that attracted them to the Zionist idea, which offered them protection. Opposition to Zionism can only be credible if it is predicated on a firm commitment to tackle and eliminate antisemitism.

Being subjected repeatedly to suspicion and hostility framed around my Jewish Israeli background has made me feel unsafe. Yet I am too much of a universalist to give up the fight against anti-Jewish hatred and to seek refuge either in a protective environment that purports to put Jewish safety above all other considerations, or in the illusion that denying antisemitism will make it go away. Antisemitism takes on a variety of forms in different historical times and contexts. Some themes replicate themselves, others are adapted. All must be confronted, including the most subtle and those that hide behind a progressive mask.

The London Centre for the Study of Contemporary Antisemitism offers a forum to “challenge the intellectual underpinnings of antisemitism in public life and to confront the hostile environment for Jews in universities”. I embrace that goal. I see it as an opportunity to have an open discussion around a range of approaches, expertise, and viewpoints. We need, in my opinion, a critical reflection that considers antisemitism in a universal context, one that connects to debates on other contemporary forms of racism such as Romaphobia, Islamophobia and the backlash of culture wars that has been a reaction to the Black Lives Matter movement. Understanding both antisemitism and the suffering brought about by the Nakba is a key to enabling constructive dialogue in Israel/Palestine. And on UK campuses we need and deserve protection from anti-Jewish stereotyping and the threats of isolation and mental abuse that come with it.